It is not too late to meaningfully address climate change, Prof Stephanie Midgley of the Western Cape Department of Agriculture told attendees to Hortgro’s technical symposium last month and in fact, she noted, many of the solutions contain opportunities for the fruit industry.

The final volume of the sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change which appeared this year focused on strategies to mitigate climate change.

The probability of the KwaZulu-Natal floods earlier this year doubled because of human-induced climate change

The probability of the KwaZulu-Natal floods earlier this year doubled because of human-induced climate change

"Many of the solutions are opportunities"

“The solutions and the technology are often already there. We just need the political will and the financing to do it. Many of the solutions are opportunities and especially in the fruit industry, there are co-benefits for human well-being, for sustainable development, environmental health and so on. So not all of these things are just going to be a drain on our resources, they’re going to make things better.”

Professor Midgley pointed out that one of those - a shift to more plant-rich diets - represents a big opportunity for the fruit industry,

She remarked that she held her first presentation on climate change 22 years ago. “Since that time we’ve learned a lot and I’m so excited that the deciduous fruit industry has taken it on board, funded the research and prioritized it. By now, there is no excuse not to act on climate change.”

The science behind climate change has been known for over a century and the evidence stares us in the face. The language used in this sixth Assessment Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is stronger than before, she noted, to convey the urgent message that the rapid and intensifying changes are occurring at a pace not seen in thousands of years.

Source: Prof Stephanie Midgley's Hortgro presentation

Source: Prof Stephanie Midgley's Hortgro presentation

“There have been warm periods before, but the last time we saw warming at these levels was more than 100,000 years ago, during the last interglacial period,” she said. “We’re reaching a very dangerous level which has not been seen since human civilisation emerged. It is indisputable that the warming has a human cause, and it’s making extreme events more frequent and severe.”

Southern Africa warming at twice global average

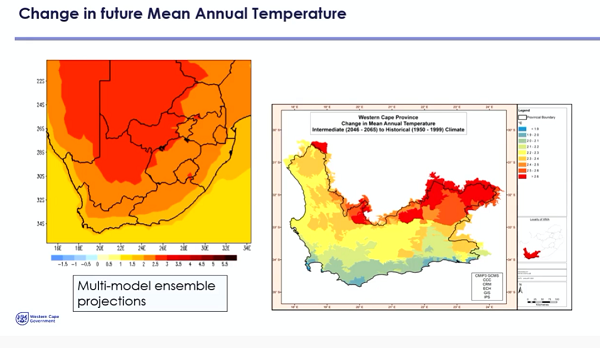

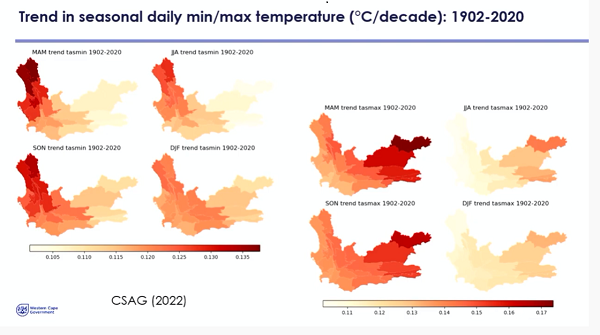

The mean global surface temperature warming has been 1.1°C at this point, relative to temperatures from 1850 to 1900, but it is higher over land (on average 1.6°C over land) and not evenly spread: Southern Africa is warming is twice the global average at this point.

At the current rate of pledges made by governments to curb emissions, we’re looking at a 2.8°C rise in temperature. If a global rise of 2°C warming is reached, that could translate to between 2.5°C and 3°C warming in Southern Africa, she said.

Source: Prof Stephanie Midgley's Hortgro presentation

Source: Prof Stephanie Midgley's Hortgro presentation

Climate change attribution science tries to link particular events to climate change and in this way, it has been found that under current climate change conditions and based on historical hydrological and meteorological models, the probability of recent extreme events rises.

The Cape’s drought was three times more probable, the KwaZulu-Natal floods twice more probable compared to without human-induced climate change. The recent heatwave over the Indian subcontinent was thirty times more probable because of climate change while the heat wave and fires in the Pacific Northwest of North America were virtually impossible without climate change.

Mid-century Western Cape: 5 or 6 years drought every decade

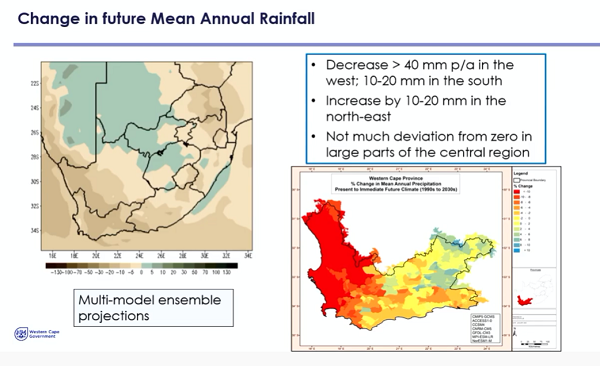

“Rainfall projection is much more difficult than temperature. The globe as a whole is going to get wetter but certain areas in the subtropics and all of the Mediterranean will get drier, in fruit production areas like Chile, California, Mediterranean Europe and the Western Cape. Droughts will become more frequent, by the mid-century probably 2.5 times more likely.”

Two studies have been done to focus on the impact on the Western Cape fruit industry, funded by Hortgro Science, which modelled scenarios for 11 different fruit regions across the province and a second, commissioned by the Western Cape Department of Agriculture and conducted by the University of Cape Town’s Climate System Analysis Group, currently being prepared for wider dissemination. Source: Prof Stephanie Midgley's Hortgro presentation

Source: Prof Stephanie Midgley's Hortgro presentation

All of the available models agree on a drying trend over the western parts of South Africa where a decrease of over 40mm per annum is projected, especially for the core winter rainfall areas.

“Probably from the early 2040s and 2050s we’ll be seeing the clear signs coming through and by the middle of the century, 5 or 6 years of every ten years could be moderate drought years in the Western Cape.”

The main area of concern is up the West Coast and Koue Bokkeveld during autumn and spring season. Rainfall shows a decreasing trend in autumn when, she said, “we’re seeing a very clear drying in autumn.”

In other parts of the country future rainfall patterns are not so clear – rainfall being more difficult to predict than temperature, she points out: there could even be an increase by 10 to 20mm in the northeast of South Africa with not much deviation over large parts of central interior.

We know very little about future hail risk, and Prof Midgley added that there could be a possible increase in wind speed in southwestern areas.

Pome fruit and stone fruit areas at risk

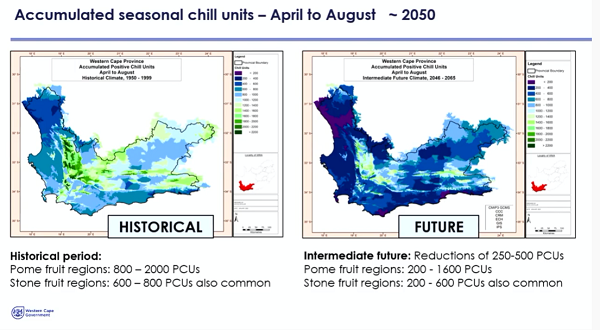

Chilling units are decreasing, with high chill units restricted to high-lying areas by 2050.

Especially in inland areas there will be an increase in high temperature stress with a high increase in daytime maximum temperatures and concomitant increased risk of sunburn risk, rising evapotranspiration and accelerated pest life cycles.

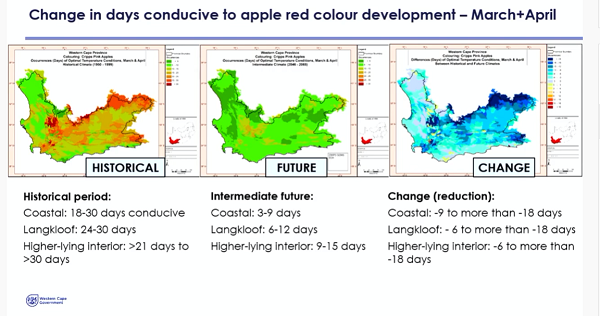

By mid-century there will be a reduction in the number of days conducive to red colour development on apples, with a reduction of between 9 and 18 days and in a coastal area like Elgin-Grabouw, that could be limited to between 3 and 9 days such days over March and April in future.

Source: Prof Stephanie Midgley's Hortgro presentation

Source: Prof Stephanie Midgley's Hortgro presentation

Elgin-Grabouw being limited by between 9 and 18 days of reduction, more so in coastal areas Elgin-Grabouw which could be limited to between 3 to 9 such days in future during March and April.

The pome fruit production areas of Elgin-Grabouw-Vyeboom-Villiersdorp and Greyton are possibly at greatest risk due to losses in winter chill units, becoming more suitable to stonefruit.

“High-lying areas (Koue and Warm Bokkeveld, the Langkloof) remain viable but they’ll have to deal with extreme hot days through sunburn protection and increased irrigation to make up for increased evapotranspiration.”

The Klein-Karoo could become even more marginal for stone fruit (it’s already a very vulnerable area) while the northern Berg River region will become “much warmer” and possibly drier than at present.

Source: Prof Stephanie Midgley's Hortgro presentation

Source: Prof Stephanie Midgley's Hortgro presentation

Higher winter chill varieties of stone fruit will need to be phased out, she advised, while all the tools in the toolbox will have to be used: soil health, regenerative agriculture and efficient irrigation strategies.

As long as humans burn fossil fuels, it will get warmer. The overall risk will, in the words of the sixth IPCC Assessment Report, “cascade across sectors and regions”.

“Climate change is going to affect everything in our lives,” Prof Midgley observed.