Avocado lovers are only too familiar with this: you buy a beautiful avocado and can't wait to get home to devour it. As soon as you get home, you cut the avocado open, just to be met with an unexpected, unwelcome sight - the fruit's flesh, near its tip, is bruised.

Hyperspectral Cabinet

In the Netherlands, Wageningen Food & Biobased Research has succeeded in developing a new method to detect avocado stem-end rot – that brown discoloring at the fruit's tip - six days before it can be seen with the naked eye. This method has the advantage that the avocado does not need to be cut open or squeezed.

Non-destructive fruit and vegetable quality measuring - because this method can be used far more extensively than just avocados - can be of great value to all the fruit and vegetable sector's phases. From growers who want to know whether their fruit is ripe enough to harvest for importers who wish to check a container's quality meets their distributors' requirements upon arrival.

Those distributors also want to monitor products' ripeness during storage at the warehouse. And what used to be and is now mostly done in a research facility could become possible in practice in the future with a handheld meter. Of course, you could also incorporate the technology into sorting lines, perhaps the most significant application.

Visible, near-infrared spectroscopy

“Our research aims to measure all kinds of quality aspects without damaging the product. We're trying to find which sensors can measure which parameters," says Eelke Westra, Postharvest Quality Program Manager at Wageningen Food & Biobased Research. "We do so with visible, near-infrared spectroscopy, an optical technique that uses electromagnetic radiation (400-2500nm) interaction with fruit."

Referential test

"Spectrum absorption lets us see many other things besides color. That's via certain chemical elements on or just below the product surface. We can observe physical properties like surface texture, firmness or particle size and chemical aspects such as moisture, proteins, starch, sugar, and oil content."

Physical and chemical properties

This research consists of two main components that, together, should lead to determining a fresh product's quality. Firstly, particular quality aspects' exact physical and chemical properties are examined. That is done product-by-product, as each variety is different.

"A ripe avocado should be soft, with enough oil, not be stringy, etc. But what is it exactly in the flesh that makes it so? What do you need to measure?" Eelke explains. And then what technology and sensors can accurately measure those underlying physical and chemical properties. Without touching the product.

“We're still trying to define what physical factors cause an avocado to ripen. You can already measure things like hardness and oil content using existing instruments. But that doesn't give you enough information to know whether an avocado is ripe. It will get you a long way, but not all the way. Discovering that is the holy grail."

Measuring throughout the chain

Each control method focuses on the product's condition at a given moment. Importers and distributors can, therefore, then decide what to do with that product. Eelke is, however, convinced that to get a better idea of a product's quality, measurements should be taken more often during an item's life cycle. "You should check things like firmness and fat and dry matter content at several points in the chain: after harvesting, upon arrival in the Netherlands, and after ripening."

"You'd have to keep datasets of each batch, not only of measurements. But also about where and how the product was grown. Also, when it was picked and at what temperature it was stored. All that affects the product's ripening behavior. That's not impossible because the possibilities of storing data and later analyzing it are increasing dramatically. And perhaps all that information already exists, just separately. Combining all that and keeping it up to date could improve the point where you take measurements on the sorting line."

"I don't think we'll reach a point where we can measure everything at once. In that sense, our research's also broad. It considers exactly what data you need to improve, say, the ripening decision. How much sunshine the orchard had could greatly affect that, or maybe it is the average morning temperatures. That's what we want to know. Then it's up the sector to collect all that information reliably and where necessary, sharing it throughout the supply chain," says Westra.

Hyperspectral measurement

The technique Wageningen Food & Biobased Research developed uses visible, near-infrared spectroscopy - an optical measuring method that has been in use for some time - as well as hyperspectral measuring. "Consider, for instance, a photograph. It gives us a two-dimensional image. Each pixel has a certain color value, and together they form the picture. That's the normal spectrum."

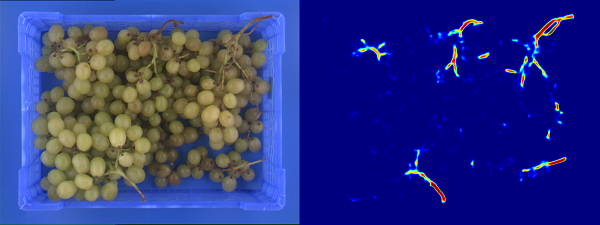

Hyperspectral image grapes

"The hyperspectral measurement reads the values within one pixel. That's no longer in the visual spectrum, but in the near-infrared spectrum and even below. Instead of a two-dimensional picture, you get a three-dimensional data set you can't convert directly into an image. But it does provide additional information," Eelke continues.

"Our latest development gives a setup that will correlate such data with practical observations, like, say, maturity levels. The entire study is still in the development stage. Our technology is around level 5-6 on the TRL (Technology Readiness Levels) scale. So we know it's possible, just not yet at a level where a major importer could purchase the technology and start using it."

Rapid, broad application

Non-damaging measurements have the advantage that the product remains intact. Reading speed and capacity will increase so that you can measure not only samples but all products in the long run. The application Wageningen researchers are developing should also become available as a cost-effective solution for all chain partners. "We have a fixed setup in Wageningen," Eelke adds.

"But we've shown that mobile equipment is a possibility, for, for instance, quality control of a container of fruit, or in the distribution center or at a wholesaler. The sensors are available. We're going to see how we can transfer our setup systems to devices you can use in practice. Both as part of a high-capacity sorting plant. And as a handheld meter for growers in the field or inspectors on the shop floor."

Wageningen's researchers are primarily focusing on all fruit varieties with this technology. By extension, vegetables, too, will be addressed, as will all kinds of products subject to quality change, such as meat. "Dairy, maybe a little less. I find liquids a little trickier," Eelke concludes.

Eelke Westra Wageningen University & Research

Wageningen University & Research

Eelke.westra@wur.nl