Three weeks have passed since Russia invaded Ukraine. It is now becoming evident how reliant the European Union is on Russia for oil and gas. That's why alternative sources and new forms of sustainable energy supply will have to be developed even faster.

At the same time, Russia does not only have large fossil fuel reserves, it also has the world's largest forest, by far. It is about 815 million hectares of woodland - almost twice the size of the Brazilian Amazon - and accounts for about 25% of the planet's forests. Now that trade with Russia has been banned, questions arise: how much timber and lumber does the EU import from Russia? To what extent it is possible to do without that?

Gert-Jan Nabuurs is a professor of European Forests at Wageningen University & Research (WUR) in the Netherlands. He and fellow WUR researchers Bas Lerink, Silke Jacobs, and Nicola Bozzolan looked into that.

European wood

According to these researchers, the answer lies in considering how much timber and lumber the European Union uses - almost 500 million m3 annually. That has been steadily increasing over the past decades, with shifting product groups and fluctuating economic growth rates. But critically, about 80% of these products come from Europe's forests.

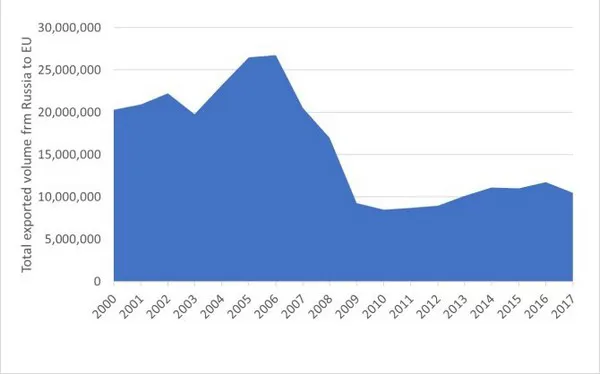

About ten percent comes from the North American continent and eight percent from South America (mainly pulp from Eucalyptus). Less than 0.2% of total usage is tropical hardwood. With currently about 10 million m3 of imports, Russia's trade to the EU makes up only about two percent of that region's total wood consumption (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. All timber and lumber exports from Russia to the EU, as a whole, since 2000.

Trade relations

You can, thus, draw a clear conclusion: the EU depends very little on Russia for its wood supply. The researchers say you can say more about this by looking at importing countries and product groups.

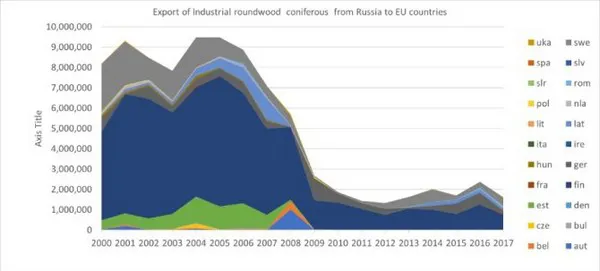

Trade relations with Russia soured around 2008 when that country imposed high export tariffs on raw spars. Volumes fell sharply (exacerbated by the economic crisis) and never recovered, as shown in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows each importing country's share of industrial spars (unprocessed logs).

Finland and Sweden used to import a lot of raw spars from Russia, so they were most affected by post-2008 trade rates. Those volumes have dropped significantly, but these two countries still import reasonable volumes. The current trade ban will, therefore, somewhat affect them.

Figure 2. Russia's top raw material export - unprocessed spars - until 2008 (to mainly Finland and Sweden) when a high export tariff was imposed.

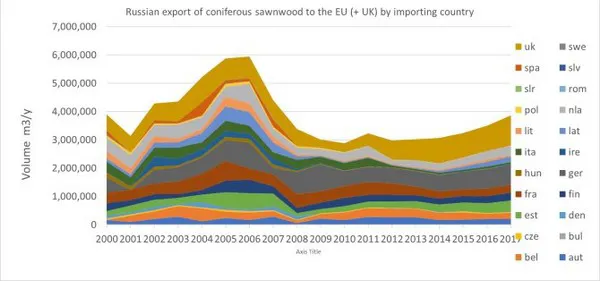

Figure 3. Processed softwood exports from Russia to the EU countries. After the economic crisis, these picked up, and volumes remain decent.

Figure 3 shows that some countries and product groups will be quite affected. There is a fairly stable, increasing trade in sawn softwood timber. Relatively large volumes go to Estonia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. The timber market is already tight, with high prices last year. The current Russian trade adds an additional challenge that other suppliers must meet. That trade boycott will affect some countries and companies, and they will have to look for other wood sources. The embargo will affect EU lumber exports too.

Potential world player

All the global wood market research indicates that Russia remains a country that could supply vast quantities of this material in the future. But according to the researchers, Russia has, so far, not succeeded in developing this. Logistical problems, poor management, and long distances have always kept it from becoming a global player. Figure 3's sawn timber quantities are paltry compared to the size of Russia's forests.

The European Union now seems to be benefitting from Russia never becoming a huge exporter. The current crisis highlights that the EU will become to rely even more than ever on its own woodland resources. That requires investing in good forest management and expansion, and education. And a good balance between biodiversity, carbon storage, and timber production.

In short, Nabuurs, Lerink, Bozzolan, and Jacobs say the European Union does not rely on Russia for its timber, but the ban has tightened that balance. They conclude that the EU should invest in its forests, manage them carefully, and gradually increase domestic production.

Source: WUR